Released in 1978, “Too Much Heaven” stands as one of the Bee Gees’ most delicate and spiritually resonant recordings. While often grouped with their late-1970s hits, the song occupies a very different emotional space from the group’s dance-driven anthems. This is not music for movement — it is music for stillness. At its heart, “Too Much Heaven” is a meditation on devotion, humility, and the fear of losing something so perfect it feels unreal.

From the opening moments, the song creates an atmosphere of reverence.

Soft synthesizer pads drift gently into view, followed by a restrained rhythm that feels more like a slow breath than a beat. The arrangement is intentionally weightless, allowing the melody to float rather than drive forward. This sonic lightness mirrors the song’s emotional theme: love as something fragile, elevated, and almost untouchable.

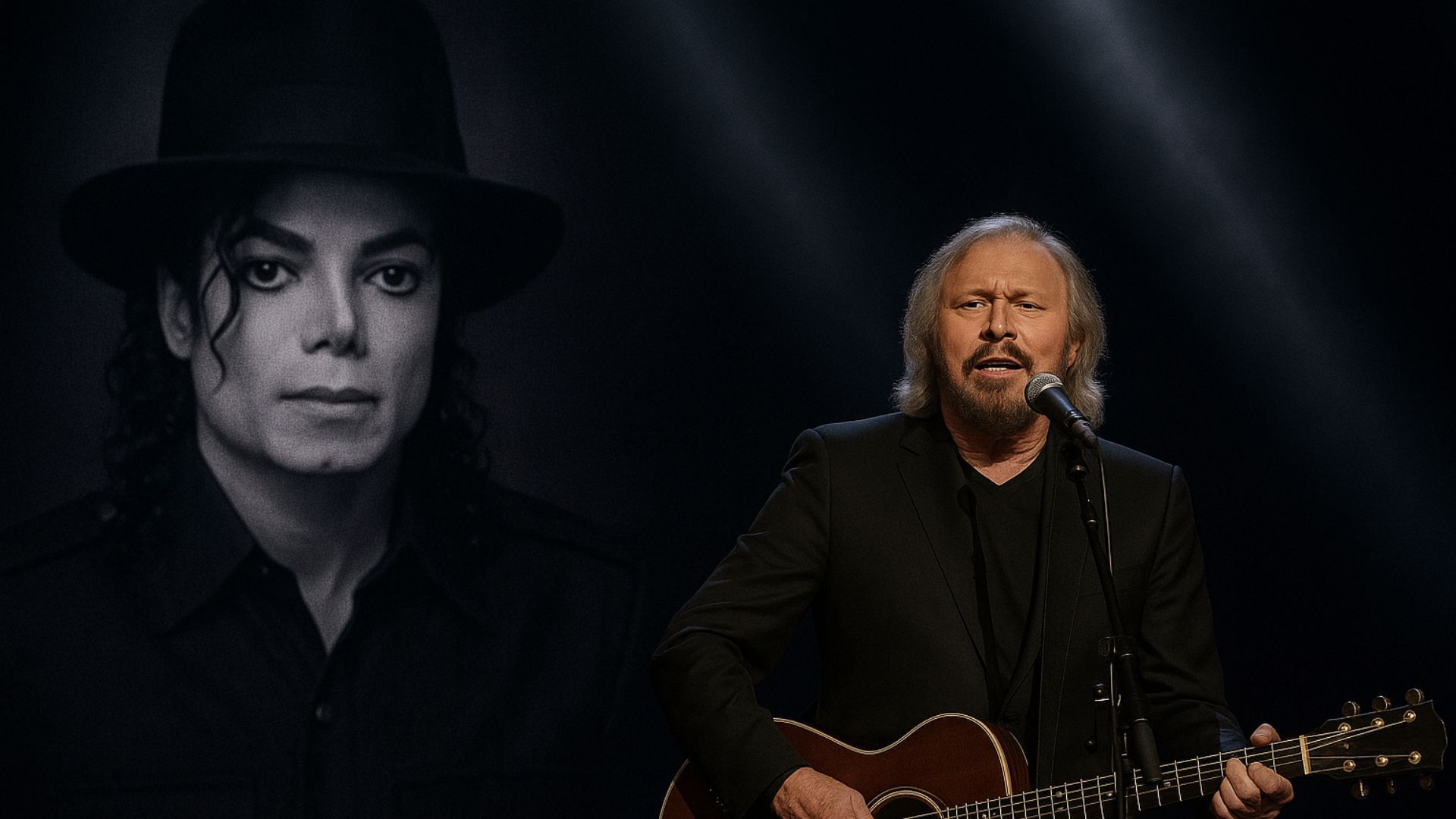

Barry Gibb’s lead vocal is among the most tender of his career.

He sings not with urgency, but with awe — as though he is standing inside an experience he cannot fully comprehend. His falsetto here is not flamboyant or dramatic; it is hushed, reverent, and intimate. Every phrase feels carefully placed, as if spoken in a sacred space where noise would break the spell.

Lyrically, “Too Much Heaven” is built on paradox.

The narrator is overwhelmed not by pain, but by abundance. Love, in this song, is so complete that it inspires fear — the fear that such perfection cannot last. This emotional tension gives the song its quiet power.

The emotional core of the track lies in its central admission:

💬 “Nobody gets too much heaven no more.”

This line suggests a deep awareness of impermanence.

The narrator understands that moments of pure connection are rare and fleeting. Rather than taking love for granted, he approaches it with humility and gratitude. Heaven here is not a place — it is a feeling, a state of being created by emotional closeness.

Musically, the harmonies play a crucial role in shaping this meaning.

Robin and Maurice Gibb’s backing vocals hover softly around Barry’s lead, creating an almost choral effect. The voices blend so seamlessly that they feel less like individuals and more like a single emotional presence. The harmonies do not rise triumphantly; they surround, reinforcing the song’s sense of protection and reverence.

The arrangement avoids dramatic climax.

There is no explosive chorus, no instrumental flourish meant to impress. Instead, the song remains suspended in calm reflection from beginning to end. This restraint is deliberate. The Bee Gees understood that emotional depth does not always require intensity — sometimes it requires quiet.

What makes “Too Much Heaven” endure is its emotional maturity.

It portrays love not as possession or certainty, but as something to be honored and safeguarded. The narrator does not claim ownership of heaven; he is grateful simply to experience it, even briefly.

Over time, the song has taken on a timeless quality.

It is played not to celebrate excess, but to acknowledge grace — the rare moments when life feels aligned, gentle, and meaningful.

Ultimately, “Too Much Heaven” is a song about reverence.

About recognizing love as something sacred.

About holding joy carefully,

knowing it cannot be forced,

only cherished.

It is Barry Gibb offering a quiet truth:

that the most powerful emotions

often speak

in whispers,

not shouts.