When the Bee Gees released “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You” in 1968, the world was still discovering how deeply dramatic, poetic, and emotionally fearless the young Gibb brothers already were. While many bands of the era leaned toward romance or rebellion, Barry, Robin, and Maurice wrote a song from a place few pop acts would dare to explore: the mind of a man facing his last hour on earth.

This was not a break-up song, not a lament, not a ballad about misunderstanding.

It was a confession.

A final heartbeat from someone trapped between what’s already done and what can never be undone.

The track opens with a tense pulse — Maurice’s bass line steady and heavy, like a clock counting down. A mournful organ fills the background, creating the sense of a small, dimly lit room. Then Barry enters, his voice trembling with quiet desperation:

“The preacher talked with me and he smiled…”

But the smile offers no comfort.

The narrator knows the truth: there is no escape, only the inevitability of his fate. He has killed a man — not out of cruelty or malice, but out of passion, out of the uncontrollable fire of the human heart. And now, with minutes left before his execution, all he can think of is her.

This leads into the emotional powerhouse of the chorus, delivered with the raw urgency only the Bee Gees could summon:

💬 “I’ve just gotta get a message to you — hold on, hold on…”

In Robin’s trembling vibrato, the line becomes almost unbearable. It is the sound of a man clawing at the last thread that still connects him to life. He is not begging for freedom. He is begging for forgiveness — for the chance to say goodbye.

The contrast between Barry’s calmer lead and Robin’s anguished second verse creates an emotional duality that defines the entire recording. Where Barry offers steadiness — acceptance — Robin brings the rising panic of a soul not yet ready to let go. Maurice, as always, holds the brothers together musically, his sensitivity underlining every shifting mood.

The orchestration intensifies as the song progresses.

-

Strings rise like desperate thoughts running out of time.

-

The percussion grows heavier, echoing the finality of footsteps approaching a cell.

-

The harmonies tighten, amplifying the weight of the moment.

But what makes this song endure is not its drama — it’s its humanity.

The narrator is guilty. He knows it.

But he is also in love.

He knows she will never hear the words he needs to say.

And yet he tries.

That simple act — the attempt to reach someone you love when time is slipping away — gives the song its heartbreaking core.

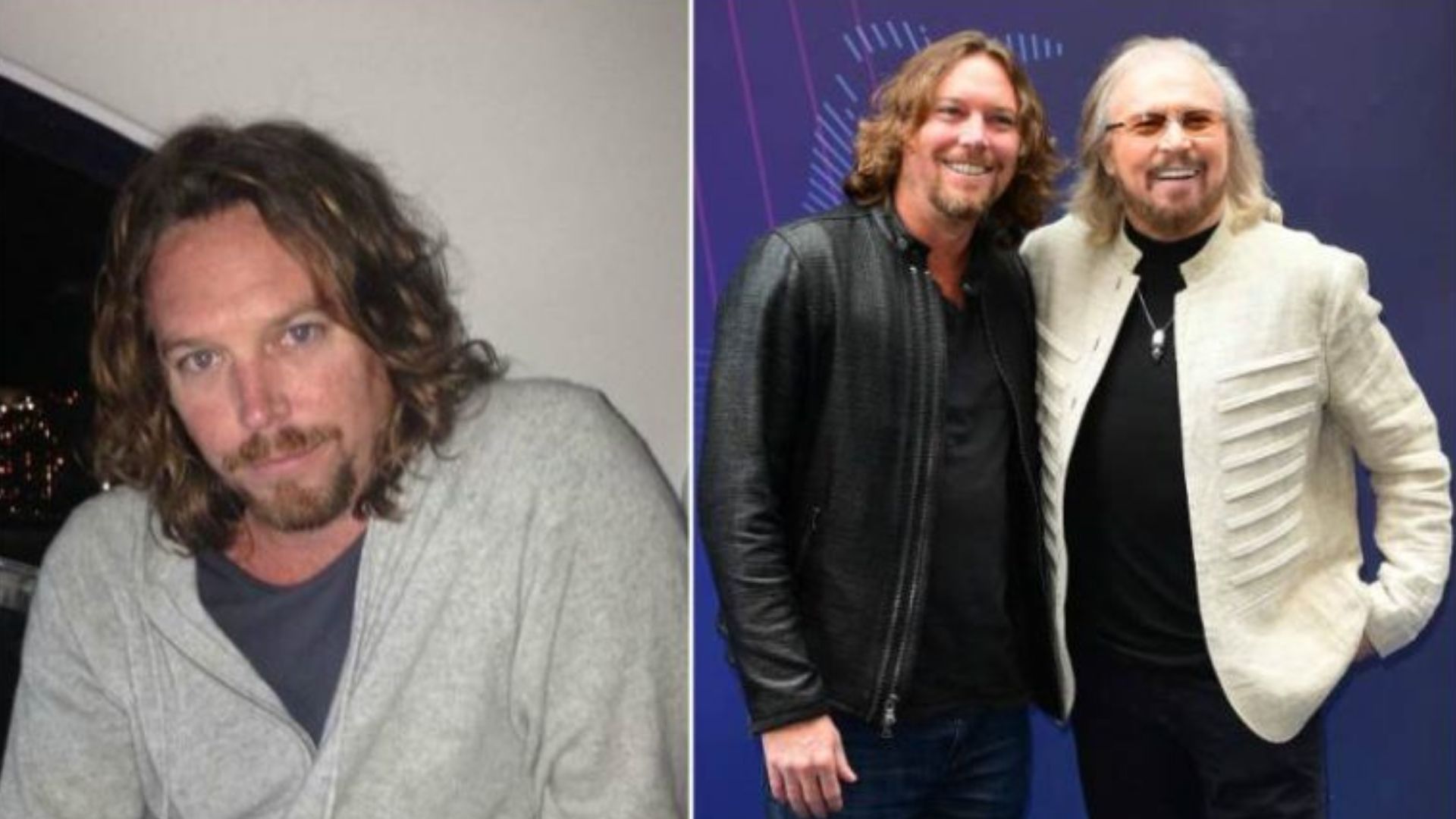

Decades later, when Barry performs “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You” alone, the meaning deepens. What was once a prisoner’s final request becomes, in Barry’s voice, a tribute to his own brothers — messages he too never got to send.

Ultimately, “I’ve Gotta Get a Message to You” is one of the Bee Gees’ most powerful achievements.

A short, devastating opera of love, remorse, and the last hope of a dying man.

A reminder that the human heart is rarely logical — but always sincere.